Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven)

| Symphony No. 9 | |

|---|---|

| Choral symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

A page (leaf 12 recto) from Beethoven's manuscript | |

| Key | D minor |

| Opus | 125 |

| Period | Classical-Romantic (transitional) |

| Text | Friedrich Schiller's "Ode to Joy" |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1822–1824 |

| Dedication | King Frederick William III of Prussia |

| Duration | about 65 to 70 minutes |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Orchestra with SATB chorus and soloists |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 7 May 1824 |

| Location | Theater am Kärntnertor, Vienna |

| Conductor | Michael Umlauf and Ludwig van Beethoven |

| Performers | Kärntnertor house orchestra, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde with soloists: Henriette Sontag (soprano), Caroline Unger (alto), Anton Haizinger (tenor), and Joseph Seipelt (bass) |

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, is a choral symphony, the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musicologists as a masterpiece of Western classical music and one of the supreme achievements in the history of music.[1][2] One of the best-known works in common practice music,[1] it stands as one of the most frequently performed symphonies in the world.[3][4]

The Ninth was the first example of a major composer scoring vocal parts in a symphony.[5] The final (4th) movement of the symphony, commonly known as the Ode to Joy, features four vocal soloists and a chorus in the parallel key of D major. The text was adapted from the "An die Freude (Ode to Joy)", a poem written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and revised in 1803, with additional text written by Beethoven. In the 20th century, an instrumental arrangement of the chorus was adopted by the Council of Europe, and later the European Union, as the Anthem of Europe.[6]

In 2001, Beethoven's original, hand-written manuscript of the score, held by the Berlin State Library, was added to the Memory of the World Programme Heritage list established by the United Nations, becoming the first musical score so designated.[7]

History

[edit]Composition

[edit]The Philharmonic Society of London originally commissioned the symphony in 1817.[8] Beethoven made preliminary sketches for the work later that year with the key set as D minor and vocal participation also forecast. The main composition work was done between autumn, 1822 and the completion of the autograph in February, 1824.[9] The symphony emerged from other pieces by Beethoven that, while completed works in their own right, are also in some sense forerunners of the future symphony. The Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, composed in 1808, basically an extended piano concerto movement, brings in a choir and vocal soloists for the climax. The vocal forces sing a theme first played instrumentally, and this theme is reminiscent of the corresponding theme in the Ninth Symphony.

Going further back, an earlier version of the Choral Fantasy theme is found in the song "Gegenliebe" ("Returned Love") for piano and high voice, which dates from before 1795.[10] According to Robert W. Gutman, Mozart's Offertory in D minor, "Misericordias Domini", K. 222, written in 1775, contains a melody that foreshadows "Ode to Joy".[11]

Premiere

[edit]Although most of Beethoven's major works had been premiered in Vienna, the composer planned to have his latest compositions performed in Berlin as soon as possible, as he believed he had fallen out of favor with the Viennese and the current musical taste was now dominated by Italian operatic composers such as Rossini.[12] When his friends and financiers learned of this, they pleaded with Beethoven to hold the concert in Vienna, in the form of a petition signed by a number of prominent Viennese music patrons and performers.[12]

Beethoven, flattered by the adoration of the Viennese, premiered the Ninth Symphony on 7 May 1824 in the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna along with the overture The Consecration of the House (Die Weihe des Hauses) and three parts (Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei) of the Missa solemnis. This was Beethoven's first onstage appearance since 1812 and the hall was packed with an eager and curious audience with a number of noted musicians and figures in Vienna including Franz Schubert, Carl Czerny, and the Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich.[13][14]

The premiere of the Ninth Symphony involved an orchestra nearly twice as large as usual[13] and required the combined efforts of the Kärntnertor house orchestra, the Vienna Music Society (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), and a select group of capable amateurs. While no complete list of premiere performers exists, many of Vienna's most elite performers are known to have participated.[15][16]

The soprano and alto parts were sung by two famous young singers of the day, both recruited personally by Beethoven: Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger. German soprano Henriette Sontag was 18 years old when Beethoven asked her to perform in the premiere of the Ninth.[17][18] 20-year-old contralto Caroline Unger, a native of Vienna, had gained critical praise in 1821 appearing in Rossini's Tancredi. After performing in Beethoven's 1824 premiere, Unger then found fame in Italy and Paris. Italian opera composers Bellini and Donizetti were known to have written roles specifically for her voice.[19] Anton Haizinger and Joseph Seipelt sang the tenor and bass/baritone parts, respectively.

Although the performance was officially conducted by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's Kapellmeister, Beethoven shared the stage with him. However, two years earlier, Umlauf had watched as the composer's attempt to conduct a dress rehearsal for a revision of his opera Fidelio ended in disaster. So this time, he instructed the singers and musicians to ignore the almost completely deaf Beethoven. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. He was turning the pages of his score and beating time for an orchestra he could not hear.[20]

There are a number of anecdotes concerning the premiere of the Ninth. Based on the testimony of some of the participants, there are suggestions that the symphony was under-rehearsed (there were only two complete rehearsals) and somewhat uneven in execution.[21] On the other hand, the premiere was a great success. In any case, Beethoven was not to blame, as violinist Joseph Böhm recalled:

Beethoven himself conducted, that is, he stood in front of a conductor's stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts. – The actual direction was in [Louis] Duport's[n 1] hands; we musicians followed his baton only.[22]

Reportedly, the scherzo was completely interrupted at one point by applause. Either at the end of the scherzo or the end of the symphony (testimonies differ), Beethoven was several bars off and still conducting; the contralto Caroline Unger walked over and gently turned Beethoven around to accept the audience's cheers and applause. According to the critic for the Theater-Zeitung, "the public received the musical hero with the utmost respect and sympathy, listened to his wonderful, gigantic creations with the most absorbed attention and broke out in jubilant applause, often during sections, and repeatedly at the end of them."[23] The audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and raised hands, so that Beethoven, who they knew could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovations.[24]

Editions

[edit]The first German edition was printed by B. Schott's Söhne (Mainz) in 1826. The Breitkopf & Härtel edition dating from 1864 has been used widely by orchestras.[25] In 1997, Bärenreiter published an edition by Jonathan Del Mar.[26] According to Del Mar, this edition corrects nearly 3,000 mistakes in the Breitkopf edition, some of which were "remarkable".[27] David Levy, however, criticized this edition, saying that it could create "quite possibly false" traditions.[28] Breitkopf also published a new edition by Peter Hauschild in 2005.[29]

Instrumentation

[edit]The symphony is scored for the following orchestra. These are by far the largest forces needed for any Beethoven symphony; at the premiere, Beethoven augmented them further by assigning two players to each wind part.[30]

|

Voices (fourth movement only)

|

Form

[edit]The symphony is in four movements. The structure of each movement is as follows:[32]

Tempo marking Meter Key Movement I Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso  = 88

= 88

2

4d Movement II Molto vivace  . = 116

. = 116

3

4d Presto  = 116

= 116

2

2D Molto vivace 3

4d Presto 2

2D Movement III Adagio molto e cantabile  = 60

= 60

4

4B♭ Andante moderato  = 63

= 63

3

4D Tempo I 4

4B♭ Andante moderato 3

4G Adagio 4

4E♭ Lo stesso tempo 12

8B♭ Movement IV Presto  . = 96[33]

. = 96[33]

3

4d Allegro assai  = 80

= 80

4

4D Presto ("O Freunde") 3

4d Allegro assai ("Freude, schöner Götterfunken") 4

4D Alla marcia; Allegro assai vivace  . = 84 ("Froh, wie seine Sonnen")

. = 84 ("Froh, wie seine Sonnen")

6

8B♭ Andante maestoso  = 72 ("Seid umschlungen, Millionen!")

= 72 ("Seid umschlungen, Millionen!")

3

2G Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato  . = 84

. = 84

("Freude, schöner Götterfunken" – "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!")6

4D Allegro ma non tanto  = 120 ("Freude, Tochter aus Elysium!")

= 120 ("Freude, Tochter aus Elysium!")

2

2D Prestissimo  = 132 ("Seid umschlungen, Millionen!")

= 132 ("Seid umschlungen, Millionen!")

2

2D

Beethoven changes the usual pattern of Classical symphonies in placing the scherzo movement before the slow movement (in symphonies, slow movements are usually placed before scherzi).[34] This was the first time he did this in a symphony, although he had done so in some previous works, including the String Quartet Op. 18 no. 5, the "Archduke" piano trio Op. 97, the Hammerklavier piano sonata Op. 106. And Haydn, too, had used this arrangement in a number of his own works such as the String Quartet No. 30 in E♭ major, as did Mozart in three of the Haydn Quartets and the G minor String Quintet.

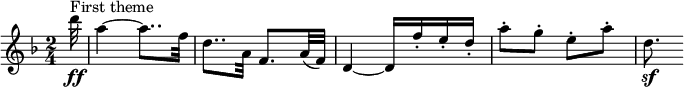

I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso

[edit]The first movement is in sonata form without an exposition repeat. It begins with open fifths (A and E) played pianissimo by tremolo strings. The opening, with its perfect fifth quietly emerging, resembles the sound of an orchestra tuning up,[35] steadily building up until the first main theme in D minor at bar 17.[36]

Before the development enters, the tremolous introduction returns. The development can be divided into four subdivisions, with adheres strictly to the order of themes. The first and second subdivisions are the development of bars 1–2 of the first theme (bars 17–18 of the first movement) .[37] The third subdivision develops bars 3–4 of the first theme (bars 19–20 of the first movement).[38] The fourth subdivision that follows develops bars 1–4 of the second theme (bars 80–83 of the first movement) for three times: first in A minor, then to F major twice.[39]

At the outset of the recapitulation (which repeats the main melodic themes) in bar 301, the theme returns, this time played fortissimo and in D major, rather than D minor. The movement ends with a massive coda that takes up nearly a quarter of the movement, as in Beethoven's Third and Fifth Symphonies.[40]

A performance of the first movement typically lasts about 15 minutes.

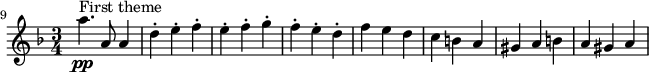

II. Molto vivace

[edit]The second movement is a scherzo and trio. Like the first movement, the scherzo is in D minor, with the introduction bearing a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the first movement, a pattern also found in the Hammerklavier piano sonata, written a few years earlier. At times during the piece, Beethoven specifies one downbeat every three bars—perhaps because of the fast tempo—with the direction ritmo di tre battute (rhythm of three beats) and one beat every four bars with the direction ritmo di quattro battute (rhythm of four beats). Normally, a scherzo is in triple time. Beethoven wrote this piece in triple time but punctuated it in a way that, when coupled with the tempo, makes it sound as if it is in quadruple time.[41]

While adhering to the standard compound ternary design (three-part structure) of a dance movement (scherzo-trio-scherzo or minuet-trio-minuet), the scherzo section has an elaborate internal structure; it is a complete sonata form. Within this sonata form, the first group of the exposition (the statement of the main melodic themes) starts out with a fugue in D minor on the subject below.[41]

For the second subject, it modulates to the unusual key of C major. The exposition then repeats before a short development section, where Beethoven explores other ideas. The recapitulation (repeating of the melodic themes heard in the opening of the movement) further develops the exposition's themes, also containing timpani solos. A new development section leads to the repeat of the recapitulation, and the scherzo concludes with a brief codetta.[41]

The contrasting trio section is in D major and in duple time. The trio is the first time the trombones play. Following the trio, the second occurrence of the scherzo, unlike the first, plays through without any repetition, after which there is a brief reprise of the trio, and the movement ends with an abrupt coda.[41]

The duration of the complete second movement is about 14 minutes when two frequently omitted repeats are played.

III. Adagio molto e cantabile

[edit]The third movement is a lyrical, slow movement in B♭ major—the subdominant of D minor's relative major key, F major. It is in a double variation form,[42] with each pair of variations progressively elaborating the rhythm and melodic ideas. The first variation, like the theme, is in 4

4 time, the second in 12

8. The variations are separated by passages in 3

4, the first in D major, the second in G major, the third in E♭ major, and the fourth in B major. The final variation is twice interrupted by episodes in which loud fanfares from the full orchestra are answered by octaves by the first violins. A prominent French horn solo is assigned to the fourth player.[43]

A typical performance of the third movement lasts around 15 minutes.

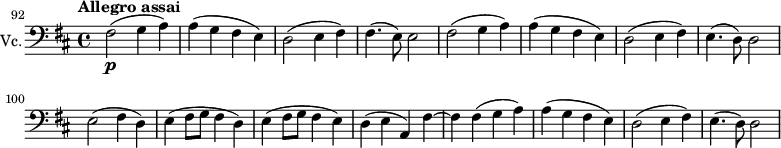

IV. Finale

[edit]The choral finale is Beethoven's musical representation of universal brotherhood based on the "Ode to Joy" theme and is in theme and variations form.

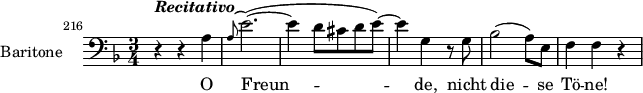

The movement starts with an introduction in which musical material from each of the preceding three movements—though none are literal quotations of previous music[44]—are successively presented and then dismissed by instrumental recitatives played by the low strings. Following this, the "Ode to Joy" theme is finally introduced by the cellos and double basses. After three instrumental variations on this theme, the human voice is presented for the first time in the symphony by the baritone soloist, who sings words written by Beethoven himself: ''O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!' Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen, und freudenvollere.'' ("Oh friends, not these sounds! Let us instead strike up more pleasing and more joyful ones!").

At about 25 minutes in length, the finale is the longest of the four movements. Indeed, it is longer than several entire symphonies composed during the Classical era. Its form has been disputed by musicologists, as Nicholas Cook explains:

Beethoven had difficulty describing the finale himself; in letters to publishers, he said that it was like his Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, only on a much grander scale. We might call it a cantata constructed round a series of variations on the "Joy" theme. But this is rather a loose formulation, at least by comparison with the way in which many twentieth-century critics have tried to codify the movement's form. Thus there have been interminable arguments as to whether it should be seen as a kind of sonata form (with the "Turkish" music of bar 331, which is in B♭ major, functioning as a kind of second group), or a kind of concerto form (with bars 1–207 and 208–330 together making up a double exposition), or even a conflation of four symphonic movements into one (with bars 331–594 representing a Scherzo, and bars 595–654 a slow movement). The reason these arguments are interminable is that each interpretation contributes something to the understanding of the movement, but does not represent the whole story.[45]

Cook gives the following table describing the form of the movement:[46]

| Bar | Key | Stanza | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1[n 3] | d | Introduction with instrumental recitative and review of movements 1–3 | |

| 92 | 92 | D | "Joy" theme | |

| 116 | 116 | "Joy" variation 1 | ||

| 140 | 140 | "Joy" variation 2 | ||

| 164 | 164 | "Joy" variation 3, with extension | ||

| 208 | 1 | d | Introduction with vocal recitative | |

| 241 | 4 | D | V.1 | "Joy" variation 4 |

| 269 | 33 | V.2 | "Joy" variation 5 | |

| 297 | 61 | V.3 | "Joy" variation 6, with extension providing transition to | |

| 331 | 1 | B♭ | Introduction to | |

| 343 | 13 | "Joy" variation 7 ("Turkish march") | ||

| 375 | 45 | C.4 | "Joy" variation 8, with extension | |

| 431 | 101 | Fugato episode based on "Joy" theme | ||

| 543 | 213 | D | V.1 | "Joy" variation 9 |

| 595 | 1 | G | C.1 | Episode: "Seid umschlungen" |

| 627 | 76 | g | C.3 | Episode: "Ihr stürzt nieder" |

| 655 | 1 | D | V.1, C.3 | Double fugue (based on "Joy" and "Seid umschlungen" themes) |

| 730 | 76 | C.3 | Episode: "Ihr stürzt nieder" | |

| 745 | 91 | C.1 | ||

| 763 | 1 | D | V.1 | Coda figure 1 (based on "Joy" theme) |

| 832 | 70 | Cadenza | ||

| 851 | 1 | D | C.1 | Coda figure 2 |

| 904 | 54 | V.1 | ||

| 920 | 70 | Coda figure 3 (based on "Joy" theme) | ||

In line with Cook's remarks, Charles Rosen characterizes the final movement as a symphony within a symphony, played without interruption.[47] This "inner symphony" follows the same overall pattern as the Ninth Symphony as a whole, with four "movements":

- Theme and variations with slow introduction. The main theme, first in the cellos and basses, is later recapitulated by voices.

- Scherzo in a 6

8 military style. It begins at Alla marcia (bars 331–594) and concludes with a 6

8 variation of the main theme with chorus. - Slow section with a new theme on the text "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" It begins at Andante maestoso (bars 595–654).

- Fugato finale on the themes of the first and third "movements". It begins at Allegro energico (bars 655–762), and two canons on main theme and "Seid unschlungen, Millionen!" respectively. It begins at Allegro ma non tanto (bars 763–940).

Rosen notes that the movement can also be analysed as a set of variations and simultaneously as a concerto sonata form with double exposition (with the fugato acting both as a development section and the second tutti of the concerto).[47]

Text of the fourth movement

[edit]

The text is largely taken from Friedrich Schiller's "Ode to Joy", with a few additional introductory words written specifically by Beethoven (shown in italics).[48] The text, without repeats, is shown below, with a translation into English.[49] The score includes many repeats.

O Freunde, nicht diese Töne! |

Oh friends, not these sounds! |

Freude! |

Joy! |

Freude, schöner Götterfunken |

Joy, beautiful spark of divinity, |

Wem der große Wurf gelungen, |

Whoever has been lucky enough |

Freude trinken alle Wesen |

Every creature drinks in joy |

Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen |

Gladly, just as His suns hurtle |

Seid umschlungen, Millionen! |

Be embraced, you millions! |

In the second last section of the text, starting from the line Brüder, über'm Sternenzelt, Beethoven goes back to the medieval sacred music tradition:[50] the composer recalls a liturgical hymn, more specifically a psalmody, using the eighth mode of the Gregorian chant, the Hypomixolydian.[50] The religious questions are musically characterized by archaistic moments, veritable "gregorian fossils" inserted in a "quasi-liturgical" structure based on the sequence first versicle – response – second versicle – response – hymn.[50] Beethoven's employment of this sacred music style has the effect of attenuating the interrogative nature of the text when is mentioned the prostration to the supreme being.[50]

Towards the end of the movement, the choir sings the last four lines of the main theme, concluding with "Alle Menschen" before the soloists sing for one last time the song of joy at a slower tempo. The chorus repeats parts of "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!", then quietly sings, "Tochter aus Elysium", and finally, "Freude, schöner Götterfunken, Götterfunken!".[51]

Reception

[edit]The symphony was dedicated to the King of Prussia, Frederick William III.[52]

Music critics almost universally consider the Ninth Symphony one of Beethoven's greatest works, and among the greatest musical works ever written.[1][2] The finale, however, has had its detractors: "Early critics rejected [the finale] as cryptic and eccentric, the product of a deaf and ageing composer."[1] Verdi admired the first three movements but lamented what he saw as the bad writing for the voices in the last movement:

The alpha and omega is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, marvellous in the first three movements, very badly set in the last. No one will ever approach the sublimity of the first movement, but it will be an easy task to write as badly for voices as in the last movement. And supported by the authority of Beethoven, they will all shout: "That's the way to do it..."[53]

— Giuseppe Verdi, 1878

Performance challenges

[edit]

Metronome markings

[edit]Conductors in the historically informed performance movement, notably Roger Norrington,[54] have used Beethoven's suggested tempos, to mixed reviews. Benjamin Zander has made a case for following Beethoven's metronome markings, both in writing[27] and in performances with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and Philharmonia Orchestra of London.[55][56] Beethoven's metronome still exists and was tested and found accurate,[57] but the original heavy weight (whose position is vital to its accuracy) is missing and many musicians have considered his metronome marks to be unacceptably high.[58]

Re-orchestrations and alterations

[edit]A number of conductors have made alterations in the instrumentation of the symphony. Notably, Richard Wagner doubled many woodwind passages, a modification greatly extended by Gustav Mahler,[59] who revised the orchestration of the Ninth to make it sound like what he believed Beethoven would have wanted if given a modern orchestra.[60] Wagner's Dresden performance of 1864 was the first to place the chorus and the solo singers behind the orchestra as has since become standard; previous conductors placed them between the orchestra and the audience.[59]

2nd bassoon doubling basses in the finale

[edit]Beethoven's indication that the 2nd bassoon should double the basses in bars 115–164 of the finale was not included in the Breitkopf & Härtel parts, though it was included in the full score.[61]

Notable performances and recordings

[edit]The British premiere of the symphony was presented on 21 March 1825 by its commissioners, the Philharmonic Society of London, at its Argyll Rooms conducted by Sir George Smart and with the choral part sung in Italian. The American premiere was presented on 20 May 1846 by the newly formed New York Philharmonic at Castle Garden (in an attempt to raise funds for a new concert hall), conducted by the English-born George Loder, with the choral part translated into English for the first time.[62] Leopold Stokowski's 1934 Philadelphia Orchestra[63] and 1941 NBC Symphony Orchestra recordings also used English lyrics in the fourth movement.[64]

Richard Wagner inaugurated his Bayreuth Festspielhaus by conducting the Ninth; since then it is traditional to open each Bayreuth Festival with a performance of the Ninth. Following the festival's temporary suspension after World War II, Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra reinaugurated it with a performance of the Ninth.[65][66]

Leonard Bernstein conducted a version of the Ninth Symphony at the Konzerthaus Berlin with Freiheit (Freedom) replacing Freude (Joy), to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall during Christmas of 1989.[67] This concert was performed by an orchestra and chorus made up of many nationalities: from East and West Germany, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, the Chorus of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and members of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden, the Philharmonischer Kinderchor Dresden (Philharmonic Children's Choir Dresden); from the Soviet Union, members of the orchestra of the Kirov Theatre; from the United Kingdom, members of the London Symphony Orchestra; from the US, members of the New York Philharmonic; and from France, members of the Orchestre de Paris. Soloists were June Anderson, soprano, Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano, Klaus König, tenor, and Jan-Hendrik Rootering, bass.[68] Bernstein conducted the Ninth Symphony one last time with soloists Lucia Popp, soprano, Ute Trekel-Burckhardt, contralto, Wiesław Ochman, tenor, and Sergej Kopčák, bass, at the Prague Spring Festival[69] with the Czech Philharmonic and Prague Philharmonic Choir in June 1990; he died four months later in October of the same year.

In 1998, Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa conducted the fourth movement for the 1998 Winter Olympics opening ceremony, with six different choirs simultaneously singing from Japan, Germany, South Africa, China, the United States, and Australia.[70]

In 1923, the first complete recording of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was made by the acoustic recording process and conducted by Bruno Seidler-Winkler. The recording was issued by Deutsche Grammophon in Germany; the records were issued in the United States on the Vocalion label. The first electrical recording of the Ninth was recorded in England in 1926, with Felix Weingartner conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, issued by Columbia Records. The first complete American recording was made by RCA Victor in 1934 with Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. Since the late 20th century, the Ninth has been recorded regularly by period performers, including Roger Norrington, Christopher Hogwood, and Sir John Eliot Gardiner.[citation needed]

The BBC Proms Youth Choir performed the piece alongside Georg Solti's UNESCO World Orchestra for Peace at the Royal Albert Hall during the 2018 Proms at Prom 9, titled "War & Peace" as a commemoration to the centenary of the end of World War One.[71]

At 79 minutes, one of the longest Ninths recorded is Karl Böhm's, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in 1981 with Jessye Norman and Plácido Domingo among the soloists.[72]

Influence

[edit]

Many later composers of the Romantic period and beyond were influenced by the Ninth Symphony.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms' Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the "Ode to Joy" theme from the last movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted "Any fool can see that!" Brahms's first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as "Beethoven's Tenth".

The Ninth Symphony influenced the forms that Anton Bruckner used for the movements of his symphonies. His Symphony No. 3 is in the same key (D minor) as Beethoven's 9th and makes substantial use of thematic ideas from it. The slow movement of Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 uses the A–B–A–B–A form found in the 3rd movement of Beethoven's piece and takes various figurations from it.[73]

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (From the New World), Antonín Dvořák pays homage to the scherzo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.[74]

Béla Bartók borrowed the opening motif of the scherzo from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to introduce the second movement (scherzo) in his own Four Orchestral Pieces, Op. 12 (Sz 51).[75][76]

Michael Tippett in his Third Symphony (1972) quotes the opening of the finale of Beethoven's Ninth and then criticises the utopian understanding of the brotherhood of man as expressed in the Ode to Joy and instead stresses man's capacity for both good and evil.[77]

In the film The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek comments on the use of the Ode by Nazism, Bolshevism, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the East-West German Olympic team, Southern Rhodesia, Abimael Guzmán (leader of the Shining Path), and the Council of Europe and the European Union.[78]

Compact disc format

[edit]One legend is that the compact disc was deliberately designed to have a 74-minute playing time so that it could accommodate Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.[79] Kees Immink, Philips' chief engineer, who developed the CD, recalls that a commercial tug-of-war between the development partners, Sony and Philips, led to a settlement in a neutral 12-cm diameter format. The 1951 performance of the Ninth Symphony conducted by Furtwängler was brought forward as the perfect excuse for the change,[80][81] and was put forth in a Philips news release celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Compact Disc as the reason for the 74-minute length.[82]

TV theme music

[edit]The Huntley–Brinkley Report used the opening to the second movement as its theme music during the run of the program on NBC from 1956 until 1970. The theme was taken from the 1952 RCA Victor recording of the Ninth Symphony by the NBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Arturo Toscanini.[83] A synthesized version of the opening bars of the second movement were also used as the theme for Countdown with Keith Olbermann on MSNBC and Current TV.[84] A rock guitar version of the "Ode to Joy" theme was used as the theme for Suddenly Susan in its first season.[85]

Use as (national) anthem

[edit]During the division of Germany in the Cold War, the "Ode to Joy" segment of the symphony was played in lieu of a national anthem at the Olympic Games for the United Team of Germany between 1956 and 1968. In 1972, the musical backing (without the words) was adopted as the Anthem of Europe by the Council of Europe and subsequently by the European Communities (now the European Union) in 1985.[86] The "Ode to Joy" was also used as the national anthem of Rhodesia between 1974 and 1979, as "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia".[87] During the early 1990s, South Africa used an instrumental version of "Ode to Joy" in lieu of its national anthem at the time "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" at sporting events, though it was never actually adopted as an official national anthem.[88]

Use as a hymn melody

[edit]In 1907, the Presbyterian pastor Henry van Dyke Jr. wrote the hymn "Joyful, Joyful, we adore thee" while staying at Williams College.[89] The hymn is commonly sung in English-language churches to the "Ode to Joy" melody from this symphony.[90]

Year-end tradition

[edit]The German workers' movement began the tradition of performing the Ninth Symphony on New Year's Eve in 1918. Performances started at 11 p.m. so that the symphony's finale would be played at the beginning of the new year. This tradition continued during the Nazi period and was also observed by East Germany after the war.[91]

The Ninth Symphony is traditionally performed throughout Japan at the end of the year. In December 2009, for example, there were 55 performances of the symphony by various major orchestras and choirs in Japan.[92] It was introduced to Japan during World War I by German prisoners held at the Bandō prisoner-of-war camp.[93] Japanese orchestras, notably the NHK Symphony Orchestra, began performing the symphony in 1925 and during World War II; the Imperial government promoted performances of the symphony, including on New Year's Eve. In an effort to capitalize on its popularity, orchestras and choruses undergoing economic hard times during Japan's reconstruction performed the piece at year's end. In the 1960s, these year-end performances of the symphony became more widespread, and included the participation of local choirs and orchestras, firmly establishing a tradition that continues today. Some of these performances feature massed choirs of up to 10,000 singers.[94][93]

WQXR-FM, a classical radio station serving the New York metropolitan area, ends every year with a countdown of the pieces of classical music most requested in a survey held every December; though any piece could win the place of honor and thus welcome the New Year, i.e. play through midnight on January 1, Beethoven's Choral has won in every year on record.[95]

Other choral symphonies

[edit]Prior to Beethoven's ninth, symphonies had not used choral forces and the piece thus established the genre of choral symphony. Numbered choral symphonies as part of a cycle of otherwise instrumental works have subsequently been written by numerous composers, including Felix Mendelssohn, Gustav Mahler, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Charles Ives among many others.

Other ninth symphonies

[edit]The scale and influence of Beethoven's ninth led later composers to ascribe a special significance to their own ninth symphonies, which may have contributed to the cultural phenomenon known as the curse of the ninth. A number of other composers' ninth symphonies also employ a chorus, such as those by Kurt Atterberg, Mieczysław Weinberg, Edmund Rubbra, Hans Werner Henze, and Robert Kyr. Anton Bruckner had not originally intended his unfinished ninth symphony to feature choral forces, but the use of his choral Te Deum in lieu of the uncompleted Finale was supposedly sanctioned by the composer.[96] Dmitri Shostakovich had originally intended his Ninth Symphony to be a large work with chorus and soloists, although the symphony as it eventually appeared was a relatively short work without vocal forces.[97]

Of his own Ninth Symphony, George Lloyd wrote: "When a composer has written eight symphonies he may find that the horizon has been blacked out by the overwhelming image of Beethoven and his one and only Ninth. There are other very good No. 5s and No. 3s, for instance, but how can one possibly have the temerity of trying to write another Ninth Symphony?"[98] Niels Gade composed only eight symphonies, despite living for another twenty years after completing the eighth. He is believed to have replied, when asked why he did not compose another symphony, "There is only one ninth", in reference to Beethoven.[99]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Presumably, Böhm meant the conductor Michael Umlauf.

- ^ The score specifies baritone,[31] performance practice often uses a bass.

- ^ The second column of bar numbers refers to the editions in which the finale is subdivided. Verses and choruses are numbered in accordance with the complete text of Schiller's "An die Freude"

Citations

- ^ a b c d Cook 1993, Product description (blurb). "Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is acknowledged as one of the supreme masterpieces of the Western tradition. More than any other musical work it has become an international symbol of unity and affirmation."

- ^ a b Service, Tom (9 September 2014). "Symphony guide: Beethoven's Ninth ('Choral')". The Guardian.

the central artwork of Western music, the symphony to end all symphonies

- ^ "Lansing Symphony Orchestra to perform joyful Beethoven's 9th" by Ken Glickman, Lansing State Journal, 2 November 2016

- ^ "Beethoven's Ninth: 'Ode to Joy'" Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Great Falls Symphony, 2017/18 announcement

- ^ Bonds, Mark Evan, "Symphony: II. The 19th century", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols. ISBN 0-333-60800-3, 24:837.

- ^ "European Anthem". Europa. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Memory of the World (2001) – Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No 9, D minor, Op. 125".

- ^ Solomon, Maynard. Beethoven. New York: Schirmer Books, 1997, p. 251.

- ^ Breitkopf Urtext, Beethoven: Symphonie Nr. 9 d-moll Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, op. 125, pbl.: Hauschild, Peter, p. VIII

- ^ Hopkins 1981, p. 249.

- ^ Robert W. Gutman, Mozart: A Cultural Biography, 1999, p. 344

- ^ a b Sachs 2010, p. [page needed]

- ^ a b Levy 2003, p. [page needed]

- ^ Patricia Morrisroe "The Behind-the-Scenes Assist That Made Beethoven's Ninth Happen" New York Times December 8, 2020. [1] access date March 12, 2020

- ^ Kelly, Thomas Forrest (2000). First Nights: Five Musical Premiers (Chapter 3). Yale University Press, 2001.

- ^ Patricia Morrisroe "The Behind-the-Scenes Assist That Made Beethoven's Ninth Happen " New York Times December 8, 2020. [2] access date March 12, 2020

- ^ Elson, Louis, Chief Editor. University Musical Encyclopedia of Vocal Music. University Society, New York, 1912

- ^ Life of Henriette Sontag, Countess de Rossi. New York: Stringer & Townsend. 1852.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael and Bourne, Joyce (1996). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford University Press, 2007.[page needed]

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. [page needed].

- ^ Sachs 2010, p. 22

- ^ Cook 1993, p. 22

- ^ Cook 1993, p. 23

- ^ Sachs 2010, pp. 23–24

- ^ Del Mar, Jonathan (July–December 1999). "Jonathan Del Mar, New Urtext Edition: Beethoven Symphonies 1–9". British Academy Review. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ "Ludwig van Beethoven The Nine Symphonies The New Bärenreiter Urtext Edition". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ a b Zander, Benjamin. "Beethoven 9 The fundamental reappraisal of a classic". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ "Concerning the Review of the Urtext Edition of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony". Archived from the original on 28 June 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ "Beethoven The Nine Symphonies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2008.

- ^ Thayer, Alexander Wheelock. Thayer's Life of Beethoven. Revised and edited by Elliott Forbes. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1973), p. 905.

- ^ Score, Dover Publications 1997, p. 113

- ^ IMSLP score.

- ^ Noorduin 2021.

- ^ Jackson 1999, 26;[incomplete short citation] Stein 1979, 106[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Young, John Bell (2008). Beethoven's Symphonies: A Guided Tour. New York: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1574671698. OCLC 180757068.

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. 28

- ^ Schenker 1992, p. 89.

- ^ Schenker 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Schenker 1992, p. 97.

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. 30

- ^ a b c d Cohn, Richard L. (1992). "The Dramatization of Hypermetric Conflicts in the Scherzo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony". 19th-Century Music. 15 (3): 188–206. doi:10.2307/746424. ISSN 0148-2076. JSTOR 746424. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Beethoven Forum. University of Nebraska Press. 1994. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8032-4246-3. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Ericson, John (10 April 2010). "The Natural Horn and the Beethoven 9 "Controversy"". Horn Matters | A French Horn and Brass Site and Resource | John Ericson and Bruce Hembd. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. 36

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. 34

- ^ Cook 1993b, p. 35

- ^ a b Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. p. 440. New York: Norton, 1997.

- ^ "Beethoven Foundation – Schiller's "An die Freude" and Authoritative Translation". Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ The translation is taken from the BBC Proms 2013 programme, for a concert held at the Royal Albert Hall (Prom 38, 11 August 2013). This concert was broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and later on BBC4 television on 6 September 2013, where the same translation was used as subtitles.

- ^ a b c d Buch 2003, p. [page needed].

- ^ "An die Freude" (Beethoven), German Wikisource

- ^ Solomon, Maynard (April 1975). "Beethoven: The Nobility Pretense". The Musical Quarterly. 61 (2): 272–294. doi:10.1093/mq/LXI.2.272. JSTOR 741620.

- ^ Letter of April 1878 in Giuseppe Verdi: Autobiografia delle Lettere, Aldo Oberdorfer ed., Milano, 1941, p. 325.

- ^ Norrington, Roger (14 March 2009). "In tune with the time". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Concert: Beethoven 9th, Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall" by Bernhard Holland, The New York Times, 11 October 1983

- ^ Recording of the Beethoven 9th with Benjamin Zander, Dominique Labelle, D'Anna Fortunato, Brad Cresswell, David Arnold, the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, and Chorus Pro Musica.

- ^ Schuller, Gunther (10 December 1998). The Compleat Conductor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-984058-8.

- ^ Sture Forsén, Harry B. Gray, L. K. Olof Lindgren, and Shirley B. Gray. October 2013. "Was Something Wrong with Beethoven's Metronome?", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 60(9):1146–53.

- ^ a b Raymond Holden, "The iconic symphony: performing Beethoven's Ninth Wagner's Way" The Musical Times, Winter 2011

- ^ Bauer-Lechner, Natalie: Erinnerungen an Gustav Mahler, p. 131. E.P. Tal & Co. Verlag, 1923

- ^ Del Mar, Jonathan (1981) Orchestral Variations: Confusion and Error in the Orchestral Repertoire London: Eulenburg Books, p. 43

- ^ Keller, James M. "Notes on the Program" (PDF). New York Philharmonic. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Stokowski conducts Beethoven : Symphony no. 9 ('Choral')", recorded April 30, 1934. OCLC 32939031

- ^ "NBC Symphony Orchestra. 1941-11-11: Symphony no. 9, in D minor, op. 125 (Choral)", NBC broadcast from Cosmopolitan Opera House (City Center). OCLC 53462096

- ^ Philips. "Beethoven's Ninth Symphony of greater importance than technology". Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ^ AES. "AES Oral History Project: Kees A.Schouhamer Immink". Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Makell 2002, p. 98.

- ^ Naxos (2006). "Ode To Freedom – Beethoven: Symphony No. 9". Naxos.com Classical Music Catalogue. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ^ Symphony No. 9, Leonard Bernstein at Prague Spring 1990 on YouTube

- ^ "The XVIII Winter Games: Opening Ceremonies; The Latest Sport? After a Worldwide Effort, Synchronized Singing Gets In" by Stephanie Strom, The New York Times, 7 February 1998

- ^ "Prom 9: War & Peace". BBC Music Events. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Gronow, Pekka; Saunio, Ilpo (26 July 1999). International History of the Recording Industry. London: A&C Black. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-3047-0590-0.

- ^ Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Nineteenth Century. The Oxford History of Western Music. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 747–751. ISBN 978-0-19-538483-3.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael. The Symphony: A Listeners Guide. p. 153. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ Howard, Orrin. "About the Piece | Four Orchestral Pieces, Op. 12". Los Angeles Philharmonic. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Bartók, Béla (1912). 4 Pieces, Op. 12 – Violin I – (Musical Score) (PDF). Universal Edition. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Matthews 1980, p. 93.

- ^ Slavoj Žižek (7 September 2012). The Pervert's Guide to Ideology (Motion picture). Zeitgeist Films.; Jones, Josh (26 November 2013). "Slavoj Žižek Examines the Perverse Ideology of Beethoven's Ode to Joy". Open Culture. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Victoria Longdon (3 May 2019). "Why is a CD 74 minutes long? It's because of Beethoven". Classic FM. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ K. A. Schouhamer Immink (2007). "Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc". IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter. 57: 42–46. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ K.A. Schouhamer Immink (2018). "How we made the compact disc". Nature Electronics. 1. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

An international collaboration between Philips and the Sony Corporation lead to the creation of the compact disc. The author explains how it came about

- ^ Brian Mitchell (16 August 2007). "Philips Celebrates 25th Anniversary of the Compact Disc". ecoustics.com. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "Huntley–Brinkley Report Theme". networknewsmusic.com. 20 September 1959. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ ""Countdown with Keith Olbermann" (MSNBC) 2003 – 2011 Theme". Network News Music. 31 March 2003. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce (15 November 1996). "TV Show Openings". EW.com. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "The European Anthem". europa.eu. 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Rhodesia picks Ode to Joy", Vancouver Sun, 30 August 1974

- ^ "Opinion | South Africa Poaches on Europe's Anthem". The New York Times. 24 November 1991.

- ^ van Dyke, Henry (2004). The Poems of Henry van Dyke. Netherlands: Fredonia Books. ISBN 1410105741.

- ^ Rev. Corey F. O'Brien, "November 9, 2008 sermon" at North Prospect Union United Church of Christ in Medford.

- ^ "Beethovens 9. Sinfonie – Musik für alle Zwecke – Die Neunte und Europa: "Die Marseillaise der Menschheit" Archived 8 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, by Niels Kaiser, hr2, 26 January 2011 (in German)

- ^ Brasor, Philip, "Japan makes Beethoven's Ninth No. 1 for the holidays", The Japan Times, 24 December 2010, p. 20, retrieved on 24 December 2010; Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Uranaka, Taiga, "Beethoven concert to fete students' wartime sendoff", The Japan Times, 1 December 1999, retrieved on 24 December 2010. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine - ^ a b "How World War I made Beethoven's Ninth a Japanese New Year's tradition". The Seattle Times. 30 December 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "10,000 people sing Japan's Christmas song". BBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ https://www.wqxr.org/story/2021-classical-countdown/ N. B. Links to previous years' countdowns can be found at the link in the reference.

- ^ "Bruckner's Te Deum: A Hymn of Praise". The Listeners' Club. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Fay, Laurel E. Shostakovich: A life. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ^ "George Lloyd: Symphonies Nos 2 & 9". Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Henriques, Robert (1891). Niels W. Gade (in Danish). Copenhagen: Studentersamfundets Førlag [Student Society]. p. 23. OCLC 179892774.

Sources

- Buch, Esteban (2003). Beethoven's Ninth: A Political History. Translated by Richard Miller. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07812-0. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008.

- Cook, Nicholas (1993). Beethoven: Symphony No. 9. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39039-7.

- Cook, Nicholas (1993b). "2. Early impressions". Beethoven: Symphony No. 9. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–47. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511611612.003. ISBN 978-0-521-39924-1.

- Hopkins, Antony (1981). The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London: Heinemann.

- Symphony No. 9, Op. 125: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free sheet music of Symphony No. 9 from Cantorion.org

- Levy, David Benjamin (2003). Beethoven: the Ninth Symphony (revised ed.). Yale University Press.

- Makell, Talli (2002). "Ludwig van Beethoven". In Alexander J. Morin (ed.). Classical Music: The Listener's Companion. San Francisco: Backbeat Books.

- Matthews, David (1980). Michael Tippett: An Introductory Study. London: Faber.

- Noorduin, Marten (17 May 2021). "The metronome marks for Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in context". Early Music. 49: 129–145. doi:10.1093/em/caab005. ISSN 0306-1078.

- Sachs, Harvey (2010). The Ninth: Beethoven and the World in 1824. Faber and Faber (Review by Philip Hensher, The Daily Telegraph (London), 5 July 2010).

- Schenker, Heinrich (1992). Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, A Portrayal of Its Musical Content with Running Commentary on Performance and Literature As Well. Translated by Rothgeb, John. New Haven, Connecticut and London, England: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05459-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Albrecht, Theodore (2024). Beethoven's Ninth Symphony: Rehearsing and Performing Its 1824 Premiere. Martlesham, Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. doi:10.2307/jj.5806809. ISBN 978-1-83765-105-4. JSTOR jj.5806809.

- Parsons, James (2002). "'Deine Zauber binden wieder': Beethoven, Schiller, and the Joyous Reconciliation of Opposites". Beethoven Forum. 9 (1): 1–53 – via Academia.edu.

- Rasmussen, Michelle, "All Men Become Brothers: The Decades-Long Struggle for Beethoven's Ninth Symphony", Schiller Institute, June, 2015.

- Taruskin, Richard, "Resisting the Ninth", in his Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Wegner, Sascha (2018). Symphonien aus dem Geiste der Vokalmusik : Zur Finalgestaltung in der Symphonik im 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

External links

[edit]Scores, manuscripts and text

- Symphony No. 9, Op. 125: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free sheet music of Symphony No. 9 from Cantorion.org

- Original manuscript (site in German)

- Score, William and Gayle Cook Music Library, Indiana University School of Music

- Text/libretto, with translation, in English and German

- Sources for the metronome marks.

Analysis

- Analysis for students (with timings) of the final movement, at Washington State University

- Hinton, Stephen (Summer 1998). "Not Which Tones? The Crux of Beethoven's Ninth". 19th-Century Music. 22 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1525/ncm.1998.22.1.02a00040. JSTOR 746792.

- Signell, Karl, "The Riddle of Beethoven's Alla Marcia in his Ninth Symphony" (self-published)

- Beethoven 9, Benjamin Zander advocating a stricter adherence to Beethoven's metronome indications, with reference to Jonathan del Mar's research (before the Bärenreiter edition was published) and to Stravinsky's intuition about the correct tempo for the Scherzo Trio

Audio

- Christoph Eschenbach conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra from National Public Radio

- Felix Weingartner conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1935 recording) from the Internet Archive

- Otto Klemperer conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra (1956 live recording) from the Internet Archive

Video

- Furtwängler on 19 April 1942 on YouTube, Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic on the eve of Hitler's 53rd birthday

- 1st mvt. on YouTube, 2nd mvt. on YouTube, 3rd mvt. on YouTube, 4th mvt. on YouTube, Nicholas McGegan conducting the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, graphical score

- Beethoven 9th on YouTube, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Riccardo Muti conductor, Camilla Nylund soprano, Ekaterina Gubanova mezzo-soprano, Matthew Polenzani tenor, Eric Owens bass-baritone, anniversary May 2015

Other material

- Official EU page about the anthem

- Program note by Richard Freed, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, February 2004

- Following the Ninth: In the Footsteps of Beethoven's Final Symphony, Kerry Candaele's 2013 documentary film about the Ninth Symphony

- Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven)

- Symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven

- Choral symphonies

- Choral compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven

- Works commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society

- Music dedicated to nobility or royalty

- 1824 compositions

- Musical settings of poems by Friedrich Schiller

- Memory of the World Register

- Compositions in D minor

- Frederick William III of Prussia